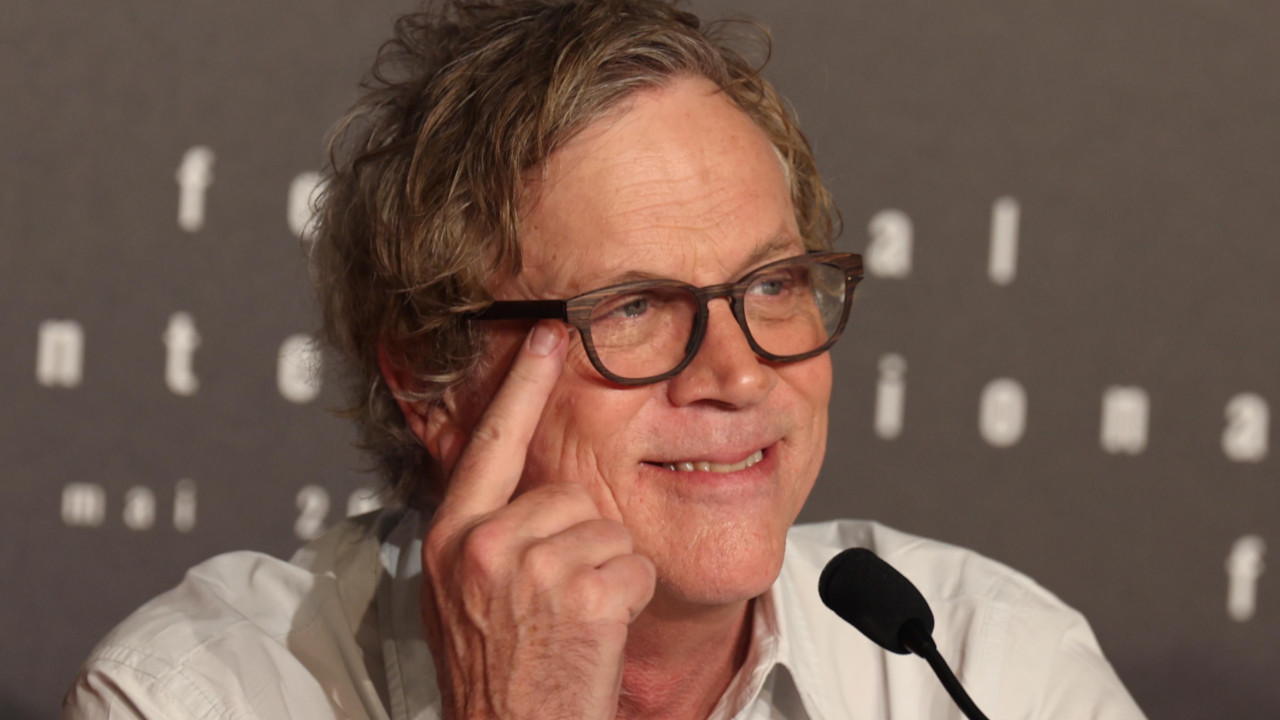

You could begin the story of Todd Haynes's Dylan movie at the very beginning, about seven years ago, while Haynes was driving cross-country in his beat-up old Honda. But since Todd Haynes's film about Dylan is as much about Todd Haynes as it is about Dylan (or maybe even more); and since Haynes is a filmmaker who, in midcareer at age 46, is doing his best to take the experimental into the multiplex; and, further, since those who don't like the film are likely to consider it a kind of gorgeous indulgence, a bizarre experiment, the temptation is to skip the ordinary narrative introduction and begin at the end, or very near the end, in this case in the last few days of filming, on the outskirts of Montreal, where, way in the back of a dark and cavernous and disused factory, there was a white glowing light, like something in a dream. We begin then with an image -- an image that is all about, believe it or not, the relationship between Haynes and his film, between Dylan and Haynes, between the artist and the subject he is trying to portray.

Todd Haynes's Dylan project is a biopic starring six people as Bob Dylan, or different incarnations of Bob Dylan, including a 13-year-old African-American boy, Marcus Carl Franklin, and an Australian woman, Cate Blanchett. It's a biopic with a title that takes it name from one of the most obscure titles in the Dylan canon, a song available only as a bootleg, called ''I'm Not There.'' As I arrived at the set outside Montreal and pulled into a mud-swamped parking lot, disembarking and moving toward the great white light, I passed through the recreated past -- namely the '60s and '70s. There was a sign for Folk City, for instance, and a fake cover for ''Bringing It All Back Home,'' a mock-up with the actress Cate Blanchett on it. There was a part of a bedroom from the '70s and, on a nearby stand, a copy of ''Les Illuminations,'' by Arthur Rimbaud, the artist who seems to have inspired Dylan in his early days nearly as much as he inspired Todd Haynes. The book, the filmgoer will learn, shows up in a scene involving the '70s superstar Dylan, a kind of jerk Dylan, played by Heath Ledger, who was just leaving the old factory: it was like a Grand Central Station of movie stars, as Ledger was on his way back to the Montreal apartment that he and the actress Michelle Williams had been staying in together for the past few weeks. Williams plays Coco Rivington, socialite, love interest of Blanchett's Dylan, who is known in the film as Jude Quinn, the electric, rebellious Dylan.

The bright light, it turned out, was the set -- a quasi-governmental interrogation scene that was, like a lot of other things in the film, never really explained -- and Christian Bale was just stepping off. Bale's Dylan is a slow-speaking folk-singer Dylan, the Dylan that seems to be searching and pondering. ''In the film I'm playing a guy on a kind of fervent quest to find the truth,'' Bale told me. He is one of the many people working on the film who has collaborated with Haynes before -- in Bale's case, in ''Velvet Goldmine,'' Haynes's homage to glam rock. So he was prepared, he said, for the audacity of the script, for so many Dylans, so many different kinds of films within one film. Whereas a lot of people in Hollywood said, ''Did you read that script?'' and scratched their heads, Bale was ready. ''I started reading the script, and I just started to laugh,'' Bale told me. He also likes the way a Haynes set works, even on this, his last day, where it all feels like the end of a race. ''With Todd's films, it's a homegrown affair,'' Bale says.

But back to the image of Todd Haynes, back to the long day, a rainy day, in a cold dark building, and into the bright blast of white light, where Haynes stepped toward the final Dylan to be filmed, the one dressed like Arthur Rimbaud, the Dylan that Haynes named Arthur, a teenage French symbolist poet, played by Ben Whishaw.

Whishaw was wearing a frayed 19th-century vest, coat and cravat. ''white-wall interrogation of a teenage poet,'' the screenplay explains. ''weaves commentary and humor throughout the film.'' Bale's scenes are shot in 16-millimeter black and white, using old Kodak film stock, in a move for authenticity -- Haynes even wanted the film in the film to look as if it were from the '60s. Time is confused, mixed; the chronology is meant to be as it is in a Dylan song. This interrogation of a teenage 19th-century poet is supposed to be taking place around 1966.

Haynes looked intense. Off the set, he is loose, laughing, gesticulating wildly or rolling a cigarette. Here he was quiet and almost preternaturally calm.

Haynes was standing in for the interrogator. He stepped forward to fix the poet Dylan's hair, adjusted his cravat, then read lines that Whishaw repeated. ''A poem is like a naked person,'' Haynes said. ''Some call me a poet. . . . A song is something that walks by itself.''

Whishaw paused. ''O.K., fidget a little,'' Haynes said. The director read on. ''We just wish to make inquiries,'' he intoned. ''Are you an illegal alien?''

''No,'' the poet replied.

''Are you an enemy combatant?''

''No.''

Let's not bother with what it all means. No one on set seemed to know for sure; they all pretty much trust Haynes that it means something. Let's focus on the camera, which Ed Lachman, the cinematographer, had lined up for a final shot of the 19th-century Dylan, a mug-shot view of the head, with the same shot of all the other Dylans, a set of Dylan mug shots accumulated over the month and a half of shooting. Together these head shots will eventually become the opening of the film: all the Dylans presented as a team, a six-actor composite. Flashing on the video monitor in Lachman's wax-pencil-drawn cross hairs were Cate Blanchett, Richard Gere, Heath Ledger, Christian Bale and Marcus Carl Franklin. Whishaw's Dylan was aligned and then filmed, after which the crew broke.

Then Hay